Keiko Nakamura

Prolife:

Associate Professor, Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA), Nagasaki University

He has served at Nagasaki University since the establishment of RECNA in April 2012. Prior to that, until March 2012, he was Executive Director of the nonprofit organization Peace Depot (Yokohama), where he worked extensively on issues related to nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation.

What is COIL?

Have you ever heard of “COIL”? It stands for Collaborative Online International Learning—an interactive educational approach where students from different countries connect online to engage in dialogue-based, collaborative learning.

Originally developed in the early 2000s at the State University of New York, COIL has gained increasing momentum in Japan since 2018, supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Various formats have emerged, including watching a lecture delivered by a professor at a foreign university and discussing it in groups, or working together on joint projects around specific themes.

While COIL has gradually expanded worldwide, its adoption accelerated significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic. With study abroad and international training opportunities drastically reduced, intercultural exchange among students became much more difficult. At the same time, rapid digitalization improved access to online tools and platforms. Against this backdrop, COIL attracted attention as a new and effective model for supporting international learning in higher education.

Even now, with international travel once again possible, the value of COIL has not diminished. In addition to its flexibility in terms of time and cost, COIL offers students valuable opportunities to engage in cross-border dialogue and deepen mutual understanding—especially in an era when diplomatic exchanges are often hindered by geopolitical tensions. In this sense, COIL continues to grow in significance as a grassroots platform for fostering dialogue and collaborative problem-solving among young people.

COIL Materials on the Issue of Nuclear Weapons

At Nagasaki University, COIL initiatives began around 2021. As a first step, the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) took the lead in developing video-based COIL materials focused on the issue of nuclear weapons. Two videos, each approximately 12 minutes long, were produced:

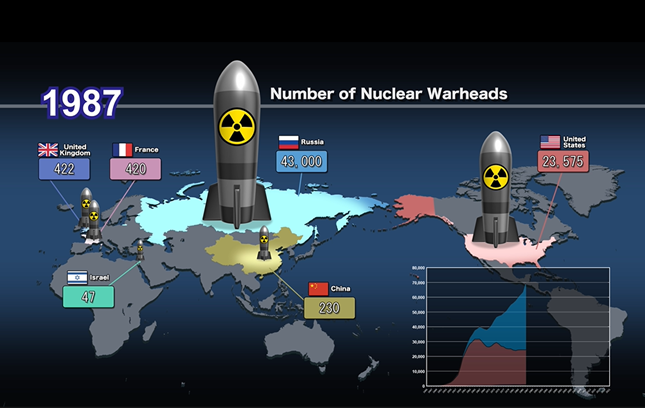

- The State of Nuclear Weapons: What Has Happened?

- A World without Nuclear Weapons: How Can We Achieve It?

The first video highlights the growing risk of nuclear weapons use in today’s global context and explores the consequences of even a single nuclear detonation, drawing on the real experience of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. The second showcases international movements toward nuclear abolition and features youth-led peacebuilding efforts.

Each video concludes with an open-ended question designed to prompt student reflection:

“Why do nuclear weapons still exist?” and “What can we do to change the world?”

A typical lesson model begins with students in Nagasaki and abroad watching the videos online at the same time. They then break into small groups to discuss the final questions. After the initial discussion, the second video is shown, followed by another round of dialogue, and the session concludes with a plenary discussion. This format can be flexibly adapted based on class size and available time.

These materials have already been used in general education courses and international workshops involving students from various countries. One of their key strengths is their ability to create a “shared foundation” for dialogue, regardless of differences in prior knowledge or experience. Since awareness of nuclear issues varies significantly across countries, regions, and individuals, the use of a common video format helps ensure that all students can engage on equal footing.

Beyond Differences in Historical Perception

However, some challenges have emerged in using nuclear weapons as a theme for international dialogue. In particular, differences in historical perception between students from Japan and neighboring countries such as South Korea and China became evident—an issue the initial COIL materials did not fully address.

To respond to this, new COIL materials were developed in the 2024 academic year in collaboration with Korean university faculty, researchers, and students. These were specifically designed to facilitate dialogue between Japanese and Korean university students.

Japanese students tend to hold a strong “nuclear taboo”—a deep-seated moral opposition to nuclear weapons. This stems largely from repeated exposure to the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki through school curricula and the media. (That said, nearly 80 years after the atomic bombings, this sentiment may be gradually fading.)

In contrast, Korean society does not share this nuclear taboo based on direct experience. In South Korea, the atomic bombings are often understood as events that contributed to liberation from Japanese colonial rule. As a result, Japan’s emphasis on its own suffering, without fully addressing its historical responsibility as a former aggressor, is sometimes met with criticism. Simply highlighting the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki without acknowledging these differences in historical memory can risk alienating rather than engaging dialogue partners.

To bridge this gap, the newly developed COIL materials take a more universal approach to the inhumanity of nuclear weapons—presenting them as a shared threat that concerns both countries. Drawing on RECNA’s “Risk Assessment of Nuclear Use in Northeast Asia,” the materials emphasize that the danger posed by nuclear weapons is a realistic and common concern for both Japan and South Korea.

The videos also introduce the little-known stories of Korean individuals who were exposed to the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Many Korean students are unaware that Koreans were among the hibakusha, making this a powerful and necessary addition. The materials conclude by calling for continued dialogue between Japanese and Korean youth and civil society, working together toward a peaceful and nuclear-free Northeast Asia.

Looking Ahead

More COIL classes using these new materials will be implemented in collaboration with Korean universities. Building on the insights and experiences gained, we also plan to develop “tailor-made” COIL materials for young people from countries with different nuclear postures—whether nuclear-armed, non-nuclear-weapon states, or those under the nuclear umbrella. Stay tuned for future developments in this vital educational initiative!